My father used to sing this song when I was little; it's the famous setting of the equally famous Kipling poem, written by American composer Oley Speaks in 1907. We were singing it today just for fun, and I decided (inevitably) to look for some versions on Youtube. The first one I listened to was the one I expected to be the perfect performance, sung by matinée-idol baritone Lawrence Tibbett, a paragon of baritonal virility; and it is great, but his fake Cockney accent just gets silly after awhile:

And then I found this.

Could anything be hipper? I love the "exotic" arrangement, and the fact that Sinatra changed "Burma girl" to "Burma broad," and, of course, Sinatra himself.

Showing posts with label Frank Sinatra. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Frank Sinatra. Show all posts

Friday, July 9, 2010

Thursday, May 6, 2010

The Baritone and I

In my recent listening to Hans Hotter, I've gotten to thinking about the baritone voice. It is, I think, the quintessential American voice. It is the most naturalistic of voice types, in the sense that it is the voice that most closely approximates the pitch of (male) human speech, and thus it can be manipulated in all kinds of ways: think of Bing Crosby's crooning, for instance, and then think of the very different male vocal style that supplanted it: the revolutionary singing of Frank Sinatra, in turns swaggeringly declamatory and beautifully, evocatively conversational. In its very naturalness, the baritone voice apotheosizes the frank, unadorned American aesthetic. I suppose it's no accident that my favorite singers are baritones: Thomas Quasthoff, Thomas Hampson, Thomas Allen (that's a lot of Thomases, come to think of it), Hans Hotter, Sinatra, Johnny Hartman.

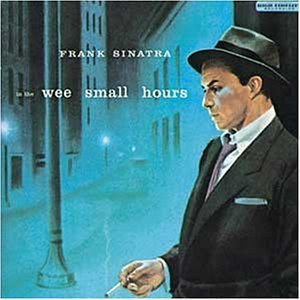

Kurt Elling's is one of the most true and beautiful American voices I know. He wrote his own preamble to a song made famous by Sinatra, "In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning." Listen carefully, and you'll hear that he makes even his breaths part of the expressive landscape of the piece. He and his pianist, Laurence Hobgood, do the song as a slow, sad waltz, with the accompaniment picking out a resigned, lonely, late-night heartbeat figure.

Oh, and if you click on the Johnny Hartman link, be sure to listen past Coltrane's introduction. The story goes that, in the recording session, Hartman was so enthralled by Coltrane's beautiful solo that he forgot to come in.

Kurt Elling's is one of the most true and beautiful American voices I know. He wrote his own preamble to a song made famous by Sinatra, "In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning." Listen carefully, and you'll hear that he makes even his breaths part of the expressive landscape of the piece. He and his pianist, Laurence Hobgood, do the song as a slow, sad waltz, with the accompaniment picking out a resigned, lonely, late-night heartbeat figure.

Oh, and if you click on the Johnny Hartman link, be sure to listen past Coltrane's introduction. The story goes that, in the recording session, Hartman was so enthralled by Coltrane's beautiful solo that he forgot to come in.

Tuesday, February 16, 2010

September Songs

In childhood, my world was saturated with the music of Beethoven and Brahms, which probably went a long way toward pushing me (as well as my two older brothers) toward a life in music. One day, however, my mother's record player broke. This happened at a time of chaos in our family life, and it remained broken for three or four Beethoven- and Brahms-less years. And then one day it was fixed, and my mother came home with an armful of LPs. The music she brought home was entirely new to us children, and altered my idea of our mother as both a listener and a person: Joni Mitchell, James Taylor, and, inexplicably, the original-cast recording of the Joseph Papp production of Threepenny Opera.

This record in particular seized my imagination in a way that can only be described as neurotic. I absconded with it to my room and played it over and over on my own garage-sale-gleaned record player. The dark landscape of Weill's music, and the tawdry underworld of Victorian England it evoked, worked their way into my imagination, until I dreamt of singing one of the wholly corrupt female roles (in college, I considered it both vindication and high praise when my vocal coach suggested this would be good repertoire for me).

In the decade or so following the Papp Threepenny, there was a minor vogue for Kurt Weill among hipsters. The marvelous, emotionally-fragile soprano Teresa Stratas released two wonderful albums of lesser-known Kurt Weill songs (the first one is pictured above), and artists like Lou Reed, PJ Harvey, and David Johansen took stabs at recreating the decadent Weimar/Weill ethos. One of my favorite bits of Weilliana is Tryout, a collection of studio recordings of Weill playing and singing his own show tunes for Broadway backers in a whispery, frail, intimate voice.

My father mentioned to me the other day that his favorite version of "September Song" (from Knickerbocker Holiday, a 1938 Broadway show about the Dutch in early Gotham) was Jimmy Durante's. I hadn't known Durante had even sung the iconic Weill classic, of which there are so many beautiful recordings, Sinatra's being the most famous. I found the Durante version on Youtube, naturally, and it is certainly worthy in its own way.

This record in particular seized my imagination in a way that can only be described as neurotic. I absconded with it to my room and played it over and over on my own garage-sale-gleaned record player. The dark landscape of Weill's music, and the tawdry underworld of Victorian England it evoked, worked their way into my imagination, until I dreamt of singing one of the wholly corrupt female roles (in college, I considered it both vindication and high praise when my vocal coach suggested this would be good repertoire for me).

In the decade or so following the Papp Threepenny, there was a minor vogue for Kurt Weill among hipsters. The marvelous, emotionally-fragile soprano Teresa Stratas released two wonderful albums of lesser-known Kurt Weill songs (the first one is pictured above), and artists like Lou Reed, PJ Harvey, and David Johansen took stabs at recreating the decadent Weimar/Weill ethos. One of my favorite bits of Weilliana is Tryout, a collection of studio recordings of Weill playing and singing his own show tunes for Broadway backers in a whispery, frail, intimate voice.

My father mentioned to me the other day that his favorite version of "September Song" (from Knickerbocker Holiday, a 1938 Broadway show about the Dutch in early Gotham) was Jimmy Durante's. I hadn't known Durante had even sung the iconic Weill classic, of which there are so many beautiful recordings, Sinatra's being the most famous. I found the Durante version on Youtube, naturally, and it is certainly worthy in its own way.

Friday, June 26, 2009

Michael Jackson, R.I.P.

My Intro to Music class had a lively discussion last spring (led by the most badass of my students, a six-foot-five senior in a do-rag whom I kicked out of class on one occasion for his disrespectful behavior, but whom I actually both liked and admired) about who was more important to music, Frank Sinatra or Michael Jackson. The indisputable answer: Michael Jackson was. As Sinatra himself said: “The only male singer who I’ve seen besides myself and who’s better than me – that is Michael Jackson.”

Jackson was one of those rare talents who approach genius, and his untimely death is truly shocking and tragic. An early biographer of the great nineteenth-century mezzo-soprano Maria Malibran wrote, in words that could just as easily apply to Jackson:

Daring originality stamped her life . . . her career as an artist, and the brightness with which her star shone through a brief and stormy

history had something akin in it to the dazzling but capricious passage of a meteor.

Requiescat in pace.

Labels:

Frank Sinatra,

Maria Malibran,

michael jackson,

Music 101

Thursday, February 28, 2008

It's Frank's World (We Just Live in It)

I'm grading my Music 101 class's first exam. In the last question, I asked them to name the piece heard so far this semester that they most enjoyed. For about eighty percent, it was Frank Sinatra's 1955 recording of "In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning" (some of the music they've heard so far includes Gregorian chant, flamenco, Yiddish ballads, chain-gang songs recorded in Georgia in the 1920's, Benny Goodman playing "Body and Soul," songs from Elizabeth Mitchell's album You Are My Little Bird, and excerpts from Die Zauberflöte). One student, a young man from Ghana, preferred the Kurt Elling version of "In the Wee Small Hours," writing (quite movingly) that Elling's "take on the song is filled with verisimilitude as he uses elements of silence, rubato, and deep emotion to portray the realism that I believe the song calls for . . . . For a moment, I felt as if I were the singer, and that I too was longing for my beloved to come back in the wee small hours." Another student's preferred class selection was "Sylvie" by Leadbelly, because, as he put it, "the blues is the backbone of rock, which is my favorite type of music." He closed his essay with what I took to be instructions to myself: "Rock on."

Labels:

Frank Sinatra,

in the wee small hours,

Music 101

Tuesday, February 5, 2008

Music 101 Smackdown

Today my students got into a heated discussion of who was the greater artist, Frank Sinatra or Michael Jackson. I have to say it’s debatable. I hastily decided to add an impromptu assignment for next class: to listen to the Jackson 5’s first hit, the 1969 “I Want You Back,” paying special attention to the astonishing emotional maturity with which the young Jackson sings the song. That kind of emotional/musical verisimilitude is the true hallmark of musical prodigy.

Friday, February 1, 2008

Music 101 in the Wee Small Hours

Thank you, Maclin Horton and Tertium Quid, for your excellent suggestions for approaching Music Appreciation (Music 101). I decided to lay aside our textbook yesterday and try to get my students to discuss what music is and what it does. I had brought in some of my own CDs to play for them: an Alan Lomax recording from 1952 of an improvised flamenco song, performed by two impoverished olive workers in Andalusia in a late-night tavern session, the only accompaniment their hands slapping the table in a complex polyrythm (Lomax notes that no one in the town could afford to purchase a guitar); a stirring Yiddish ballad from the turn of the twentieth century by the sweatshop worker/poet Morris Rosenfeld, called “The Exiles’ March”; and the song “In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning,” from the legendary album of the same name by Frank Sinatra. What I was trying to suggest to my class was the notion that music’s job, in essence, is to convey to the listener emotional meaning whose impact is immediate, and that yet almost all music does so by using forms and formulas -- that music is art and not life, and that its imitation of life is based on certain formal structures. Even the passionate fandango improvised in the tavern in southern Spain used certain standard folk poetic verse forms and flamenco singing devices. I was gratified that my students really liked the Spanish number, and that the Yiddish song, which would seem to have a narrow appeal, touched them deeply, especially the black students who make up the majority of the class, some of whom compared it to African-American slave songs. I was disappointed, however, that the great, great Sinatra song seemed at first to offer them no way into its special world. To me the song is perfection itself. The slickness of the production and the lushness of the Nelson Riddle orchestra notwithstanding, the economy of the tune, the tragic irony of the lyrics (with their terse and brilliant use of the second person), and the subtlety of Sinatra’s singing make this number far more heartbreaking – in other words, far more effective – than it would seem to be.

In the wee small hours of the morning,

While the whole wide world is fast asleep,

You lie awake and think about the girl

And never ever think of counting sheep.

When your lonely heart has learned its lesson --

You’d be hers if only she would call --

In the wee small hours of the morning,

That’s the time you miss her most of all.

I suppose that the Sinatra/Riddle aesthetic is far removed from what we listen to today, and young people only encounter it when it’s offered with postmodern self-consciousness, so it's not suprising that the class didn't immediately grasp the art of “In the Wee Small Hours.” But I played it a second time, asking my students to listen actively and try to determine what Sinatra did that made the song work. Finally one young man offered this analysis: Sinatra, he ventured, started each phrase with a crescendo, and ended each phrase with a descrescendo, which suggested initial hope emptying out into resignation. I was impressed and delighted. Those of you who know the song, isn’t that exactly what he does? Those of you who don’t know it, you're missing one of the great works of art of the twentieth century. find it on iTunes – you’ll love it.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)