The other day, while looking at the catalogue from the recent Bonnard exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum, I read a reference to his friend and colleague Édouard Vuillard's "touching small narratives of the 1890s and their poetic visions of an inward life routinely spent."

I thought that was burnished prose, the kind of phrase I might write in my dreams. But not just that; it also described something that I've been turning over in my mind, dreaming and awake, for as long as I can remember: the meaning of a good life and how it is spent.

When I was an undergraduate studying classical voice, this question prompted me to leave school for a while. I was, like so many undergraduates before me, in search of something more "real," more authentic, than what was all around me (mainly my fellow undergraduates engaged in the various bad behavior and poor choices made by undergraduates, and faculty preoccupied with other things). I had stirring ideas about how things really ought to be. I imagined, for instance, that Schubert's great song "Gretchen am Spinnrade" could be dramatically improved with an avant-garde, Sprechstimme interpretation (though I never sang it this way myself), for how can one describe the sensation of an obsessive love that is driving one mad with a modality as stylized and, let's face it, square, as classical vocal delivery? And, like Meghan Daum in her much-read New Yorker essay "My Misspent Youth," I believed that one's integrity was somehow connected to what one owned, and that if I had the right lamp and the right bowl (though "right," to me, always suggested provenance from a thrift shop), I would somehow have the right life. (I'm happy to say I did not go quite as far in this belief as one of my college classmates, who claimed that you could tell if someone was a really good musician by the clothes he or she wore.) One summer I decided not to return to school. I would have a "real" life. I had fallen in with a bunch of avant-garde theater artists, and I started performing with them and working in restaurants. Notwithstanding the fact that such experiments were thirty years out of date, I began making my own deck of tarot cards that I would use in performance, developing chance-based theater pieces based on an arbitrary lexicon of sounds, words, and gestures that I would assign to each card (fortunately, I never finished my deck). I had to do something more relevant, I thought, than sing. What did classical singing matter?

A couple of years after this extremely disorderly period in my life, I met my first husband. He himself was an artist, and he encouraged me to disengage myself from the self-indulgent silliness that passed, in my mind, for serious work, and to recommit myself to what I truly did well. With him I learned the rigorous discipline that would serve me so well throughout the rest of my life. But part of me still railed against the staid, bourgeois ethos of classical singing, and wondered if such a near-obsolete art form really mattered.

Whether it mattered or not, though, I loved it, and I kept doing it. I had a small career as an opera singer, and a somewhat bigger one as a recitalist; my real love was, and still is, the classical recital repertoire. My recital work began more and more to be based on my research into obscure and forgotten genres of art song, and my growing love for this research eventually led me to my doctoral program.

In the interstices of one's daily work and activities, though, are one's dreams, one's delusions, one's hopes, and one's failings. I always loved that terrible line in "You're So Vain" about "clouds in my coffee," because it rang true for me. There is one's morning coffee, and there are the clouds, the dewdrops, the landscapes and the weather of the imagination that inform it and the act of sitting at the kitchen table and drinking it. I wanted to be mindful of that act, and of every act.

One's mindfulness, though, can itself become an obsession and a delusion. When one is focused on the meaning behind the act and the thing, one is prone to investing the act and the thing with meanings that they do not possess. One can then so easily fall into the trap of self-aggrandizement, the illusive notion that acts and things open their meaning to oneself alone, even the fantasy that life is about reading the true meaning of phenomena, the act behind the act, the breathing soul at the heart of the thing. And this can lead, at best, to neglecting one's unpleasant chores and mundane vows, and, at worst, to madness.

What, then, is a good life well spent? How does one execute one's diurnal responsibilities without neglecting the beauty that somehow infuses everything? How does one honor that beauty without leaving reality behind?

I think the Catholic Church is extremely wise to have given us a sacramental understanding of the world and its phenomena. To acknowledge that the commonest of things can be a vehicle for divine grace is truly revolutionary, out-Buddhas Buddhism, and is a stance I need in order to resist getting sucked up daily into a whirlwind of despair. If only everyone who craved beauty and knowledge could find it in the Sacraments, the world would truly be transformed.

The frustrations of my daily life now, too, make the glimpses of beauty so much more precious. Sometimes God speaks to us in ways that are startlingly direct, but most of the time He is maddeningly silent. The memory of the startling directness can sometimes be just enough to get us through the long periods of lonely silence.

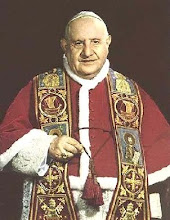

(Image above: Madame Vuillard Refilling a Carafe, 1914.)